“Reckless and incompetent expounders of holy Scripture bring untold trouble and sorrow on their wiser brethren” Saint Augustine of Hippo, Commentary on Genesis, ca. 400 AD

How do you discuss evolution and Earth science with biblical creationists, in such a way as to lead them to question their beliefs, rather than digging in deeper? This is the central problem for the book that I am now at last writing, and I would greatly value comments.

If we want to engage biblical literalists in meaningful discussion, we need to use arguments that make sense from the literalists’ point of view. As Lakatos pointed out, scientists will not abandon a position, despite anomalies, until a more satisfactory one is offered. Why should the creationist be any different? It is not enough to point to the scientific evidence. It is not even enough to point out that Noah’s Flood, using biblical chronology, would have come just in time to drown the pyramid-builders. We need to do more than simply raise objections. We must offer a better alternative, better, that is, on the creationist’s terms, emotionally and spiritually. Such an alternative, I argue, is what emerges from textual and historical analysis.

It helps, I think, to dispel the myth that religious belief requires belief in a young Earth, and the rejection of evolution, and one way of doing this is to point out that most religious believers, in the West at least, do accept, and have contributed to, the science. Since the early 19th Century, biblical believers have been among prominent proponents of scientific geology and, later, of evolution. Most Christians belong to denominations that accept the fact of evolution, and there is an organisation, the Clergy Letter Project, dedicated to the celebration of evolution as part of God’s handiwork, a position sometimes referred to as theistic evolution. There are organisations, such as the American Scientific Association, devoted to accommodating religious beliefs to the science, and a large literature on the subject. Creationists, however, are either unaware of this activity, or reject it as incompatible with their more fundamental beliefs.

The creationist argument is simple: the Bible (including in particular Genesis) is the word of God, God tells the truth, therefore the Bible is true. What could be wrong with that, from the point of view of the believer?

Plenty.

However inspired the writers of Genesis may have been, they were of necessity people of their own times, expressing themselves within their own cultural context. This is hardly a novel observation. It goes back at least to Maimonides, 12th Century biblical commentator and philosopher.

However inspired the writers of Genesis may have been, they were of necessity people of their own times, expressing themselves within their own cultural context. This is hardly a novel observation. It goes back at least to Maimonides, 12th Century biblical commentator and philosopher.

And what a context! The Old Testament text itself refers to many books that are now lost to us. The biblical Flood narrative itself shows signs of being formed from the welding together of two separate accounts written from different viewpoints, while its literary antecedents, and the antecedents of numerous other biblical passages, go back long before the date ascribed to Moses.

Bronze head of Sargon(?), unearthed at Nineveh. Public domain via Wikipedia

You are probably familiar with the story of Moses in the bulrushes, and may have wondered where on earth it came from. Here’s your answer. It is a direct echo of the story of Sargon of Akkad (2270 – 2215 BCE). Sargon’s mother, he tells us, was a priestess, and therefore had no business having children. So she made him a reed basket sealed with bitumen, and placed him in the river, from which he was rescued by a farmer drawing water.

Consider also the Code of Hammurabi, around 1754 BC. This code, and many subsequent cuneiform tablets, resemble in their “If a man…” format the codes of Exodus and Deuteronomy, including the notorious “an eye for an eye”, which the Jews by rabbinical times had reinterpreted as a right to financial compensation for injury. And the part-mythical, part-historical Sumerian Kings List (ca. 2000 BCE) assigns enormously long lives of the pre-Flood rulers, as Genesis does to its pre-Flood patriarchs.

Hammurabi receiving insignia from a seated god (Shamash, the Sun God, or Marduk); from Louvre stele of the Code, ca. 1750 – 1790 BCE. Image Mbtz own work via Wikipedia

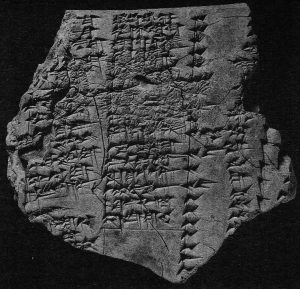

The Flood story itself exists in numerous versions, the oldest ones known to us being the Sumerian Flood of Ziusudra and the Old Babylonian (Akkadian) of Atrahasis, from around 1600 BCE, although the story may by then already have been ancient. We should also remember that our cuneiform libraries are sadly incomplete, and in several key texts the ending is missing. Even so, the resemblance is clear, and sometimes extends to specific details. On one Old Babylonian tablet, the god who warns Atrahasis says that he will send him the animals to wait at his door to be rescued. Compare Genesis 6:20, where two of every sort will come of their own accord to Noah, thus answering the question of how he would have been able to round them all up. The same tablet even uses the expression “two by two”, as in Genesis 7:9, as does another recently translated tablet, the “Ark tablet” from around 1750 BCE, that shows the Ark as an enormous coracle.

Coracle on the Tigris in Baghdad, 1914. Freddy Khalastchy via Wikipedia

Closest to the biblical account among the surviving materials is the story of Utnapishtim, embedded in the Assyrian Epic of Gilgamesh, which I finally got around to reading this year. part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal.

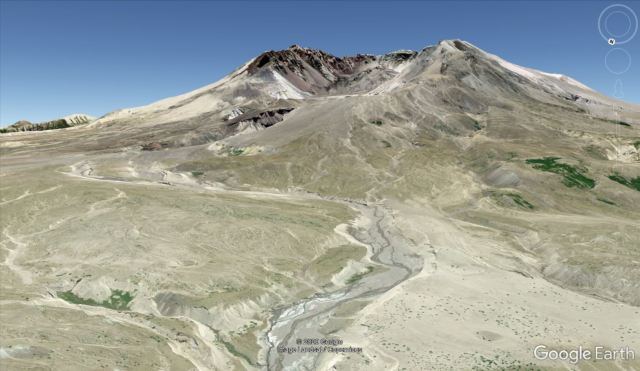

Young Earth Creationists (YECs) argue from the rapid and dramatic events observed at the Mt St Helens 1980 eruption to the conclusion that the Earth’s geological record, as displayed for example at the Grand Canyon, could be the results of the even more dramatic events associated with a biblical worldwide flood. Geochristian, in the post I link to below, dismantles specific examples of this claim, and goes on to challenge the view that the Bible describes Noah’s Flood as a worldwide catastrophe anyway. Illustration: Step Canyon, Mt St Helens; Google Earth via Geochristian

Young Earth Creationists (YECs) argue from the rapid and dramatic events observed at the Mt St Helens 1980 eruption to the conclusion that the Earth’s geological record, as displayed for example at the Grand Canyon, could be the results of the even more dramatic events associated with a biblical worldwide flood. Geochristian, in the post I link to below, dismantles specific examples of this claim, and goes on to challenge the view that the Bible describes Noah’s Flood as a worldwide catastrophe anyway. Illustration: Step Canyon, Mt St Helens; Google Earth via Geochristian Credit: USGS, Robert Krimmel, public domain

Credit: USGS, Robert Krimmel, public domain

On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. This includes the central figure acting on orders from a god, taking samples of all living things into the Ark, sealing it watertight with pitch (which is abundant in Mesopotamia), sending birds out of the Ark to test for dry land when, after the flood, it runs aground, and offering up sacrifice on emergence. In Genesis, famously, we have God pointing to the rainbow as a sign that He will never again bring on a universal flood. In the parallel passage in Gilgamesh, the goddess Ishtar displays her bejewelled necklace and says that she will never forget this time. There is a final element in Gilgamesh that is completely absent in Genesis. Enlil, who was primarily responsible for the Flood, is persuaded by the other gods that he has rather overdone it, goes down into the Ark, takes Utnapishtim and his wife by the hand, and grants them eternal life. (In Genesis, you may recall, Noah goes and gets drunk.)

On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. This includes the central figure acting on orders from a god, taking samples of all living things into the Ark, sealing it watertight with pitch (which is abundant in Mesopotamia), sending birds out of the Ark to test for dry land when, after the flood, it runs aground, and offering up sacrifice on emergence. In Genesis, famously, we have God pointing to the rainbow as a sign that He will never again bring on a universal flood. In the parallel passage in Gilgamesh, the goddess Ishtar displays her bejewelled necklace and says that she will never forget this time. There is a final element in Gilgamesh that is completely absent in Genesis. Enlil, who was primarily responsible for the Flood, is persuaded by the other gods that he has rather overdone it, goes down into the Ark, takes Utnapishtim and his wife by the hand, and grants them eternal life. (In Genesis, you may recall, Noah goes and gets drunk.)

Sources: This piece was triggered by reading Sanders’ 1960 translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh. Reading this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books,

Sources: This piece was triggered by reading Sanders’ 1960 translation of The Epic of Gilgamesh. Reading this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books,