Blog Archives

The Church, education, and “Christian values”; another bad reason for denying democracy

Reminder: there is still time to show support for our petition to abolish Church appointees on Local Authority Education Committees; just click here and fill in your details

Summary: Religious values, unless they are also shared human values, will be important to those who want to follow that particular religion, but have no special significance for the rest of us.

The Churches refer to “Christian values”, in order to justify their uninvited presence on Council Education Committees. Like other reasons offered (see earlier post), this one repays closer examination.

The Church of Scotland enjoins its appointees to assert their presence “by exercising your statutory right and endeavouring to influence council education policies in areas of interest to the national church, including the development of the curriculum, Christian values, religious and moral education and religious observance in schools”. I have already discussed the implications for the curriculum and for religious and moral education and religious observance. Here I would like to concentrate on the concept of Christian values, and, indeed, religious values in general. Read the rest of this entry

How the Church of Scotland justifies its unelected Education Committee appointees; assumption, presumption, and privilege

Our petition to the Scottish Parliament seeking to remove these unelected representatives is still open for signature here

As regular readers will know, moves are afoot to remove the three Church nominees who sit, with no regard to the electoral process, on every Local Authority Education Committee in Scotland (you can help by simply signing our Parliamentary Petition here).

In England, the legal requirement is for two such representatives, one from the Church of England and one from the Catholic Church. Something ought to be done something about this, although the English educational system, disrupted and fragmented, is now largely out of the hands of the local authorities anyway. There is much be said about the situation developing in England, little of it complimentary, but that is not my present concern.

Schisms and mergers among Scottish churches since the Reformation; Wikidwitch via Wikipedia. Click on link for clearer image

The requirement for three church appointees reflects the fractious history of Scottish Protestantism, and the presence of these representatives is a relic of the Churches’ historical input. The representatives exert power on local authorities’ most important committees, their Education Committees, over and above the power they would exert as citizens, and the Churches to which they are answerable thereby exert power over and above the power that they certainly exert, and in a democratic society must be free to exert, as associations of individuals. This is not about religion; it is about power. It is not about rights; it is about privilege.

Consider the Church of Scotland’s own code of practice for its religious representatives, which states: Read the rest of this entry

Church Appointees on Scotland’s Education Committees (as of Summer 2015)

Church Appointees on Scotland’s Education Committees (as of Summer 2015)

We are in the course of updating this information to Spring 2017. We have confirmation from all Councils who have responded to date that the Church representatives do have the right to vote in the Education Committees that they sit on.

We give here the names, Church affiliations, and appointments procedure, of the Church Appointees on all of Scotland’s Council Education Committees, as determined by Freedom of Information requests during Summer 2015. Church of Scotland and Catholic appointees are appointed by their Church hierarchies and Councils have no chioce in the matter. Procedures vary by Council for selecting the Church allowed to nominate the third appointee.

Notes on appointment procedures:

(a) Church was sole applicant in response to advertisement (8 Councils)

(b) Position vacant, pending reply from nominating Church (2 Councils)

(c) No replies to advertisement. Sitting member agreed to continue in place (1 Council) Read the rest of this entry

Church seats on Education Committees; your help needed NOW

Church of Scotland in General Assembly. This Church, the Catholic Church, and one other in your area, each nominate one member to your local Education Committee

This is not about religion. It is about power.

If you think it is right that three unelected Church nominees should sit, by law, on every Council Education Committee in Scotland, please ignore this post.

If you think it is wrong, and want to do something about it, please sign and share this petition:

https://www.humanism.scot/what-we-do/policy-campaigns/enlighten-up/

You will find more about these unelected Church nominees, and how they are shielded from democratic accountability, here.

The petition is organised by my good friends at Humanist Society Scotland, who tell me that they will be engaging with all the MSPs and candidates in the run-up to the election, and that the petition is aimed at MSPs and candidates. It runs as follows:

I believe that all members of local education committees should be accountable to their communities through the ballot box.

Local councillors are elected to represent the views of their communities. It is inconsistent with the principles of local democracy to have unelected religious leaders.

The current requirement for religious representatives stems from a reorganisation by the Westminster Government of 1973. It is time for the Scottish Parliament to consider these aspects of local democracy.

It is undemocratic to appoint members of particular religious communities to education committees without a mandate from local voters.

Previous efforts to change this law have failed because of opposition by a small band of well-organised constituents. The response must be to show our lawmakers that we are a constituency too.

I repeat; please sign and share

Religious privilege in Scottish schools increasing, says Glasgow University report

Denominational schools in Scotland are run according to a century-old Concordat between the British government and the Catholic Church. During that century, the influence of the other Churches within non-denominational schools has grown, even as their worshippers deserted them. The result is a mosaic of mutually contradictory objectives and provisions. Our children deserve better.

Glasgow University has just published its long-awaited report, sponsored by Humanist Society Scotland, into the role of religion in Scots law. The full report runs to 355 pages, and the summary to 11. It is limited to discussion of the law, but my commentary here also includes in some places what is known about actual practice. I will concentrate on the three areas covered are greatest length; the legal status of the Church of Scotland, religion and marriage, and, above all, education. The report covers several other areas where the law gives special recognition to religion. There are, for example, some tax advantages for ministers in accommodation provided by their Church, but these are minor matters in comparison.

Glasgow University has just published its long-awaited report, sponsored by Humanist Society Scotland, into the role of religion in Scots law. The full report runs to 355 pages, and the summary to 11. It is limited to discussion of the law, but my commentary here also includes in some places what is known about actual practice. I will concentrate on the three areas covered are greatest length; the legal status of the Church of Scotland, religion and marriage, and, above all, education. The report covers several other areas where the law gives special recognition to religion. There are, for example, some tax advantages for ministers in accommodation provided by their Church, but these are minor matters in comparison.

Firstly, what about the Church of Scotland? Is it, for instance, an established church? And what beliefs does it subscribe to? There is no consensus on this. The 1921 Declaratory Act, which was supposed to resolve this issue, contains an attachment in which the Church describes itself as “a national Church representative of the Christian faith of the Scottish people”, but since almost all its privileges are shared with other denominations, it is not clear what, if anything, this means. Church of Scotland ministers are automatically entitled to solemnise marriages, but since celebrants may just as easily come from other denominations, and even from groups such as the Humanists, this distinction is purely ceremonial. The Sovereign is represented at the Church’s General Assembly, and while she worships as an Anglican at Windsor, she attends Church of Scotland services when at Balmoral. However, she does not choose the Moderator, whereas she does, notionally and on the advice of the Prime Minister, choose the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Church of Scotland subscribes to the Westminster Confession (apart from its anti-Catholic clauses, which it removed in 1986). Thus it is nominally committed to the belief that I, and most of my readers, will be physically tormented in hell for eternity and serve us right. It has, however, declared itself free to interpret (i.e. ignore) its own doctrine. A saving grace, if I may so put it.

The area where the legal connections between church and state has the greatest practical importance is education, and this is the one area where is the entrenched power of religion has actually grown over time. The Scottish publicly funded school system arose in two steps, the 1872 nationalisation of schools that had hitherto been the responsibility of Presbyteries, and the 1918 nationalisation of the Catholic school system. The first of these led to the establishment of notionally non-denominational schools, in whose running the churches did not have a formal role, while the latter led to the establishment of denominational schools, within which the power of the denominational hierarchy was formidable. I was surprised at how well entrenched religious privilege has since become, in non-denominational as well as in denominational schools, how recent much of this privilege is, and how much it conflicts with the principles of a democratic state.

The 1929 Local Government (Scotland) Act, Para. 12:4, required Local Authority Education Committees to include two representatives of religion, chosen by discussion among local churches. The current requirement, for three such representatives – one Church of Scotland, one Catholic, and one other – was only formalised in 1973 (here, Sec. 124, repeated here in 1994, Sec. 31. Notice the increase in the number of representatives, and the clearer formal role of the two favoured specific denominations. Notice also that all this is pre-devolution.

St Andrew’s Cathedral, seat of the Catholic Archbishop of Glasgow

The Church of Scotland and the Catholic Church each have one nominee on the General Teaching Council, the professional body responsible for maintaining standards of training and conduct among schoolteachers (here, Schedule 2).

For denominational schools, Parent Councils are required by 2006 legislation (here) to include at least one nominee of (note the choice of words) “the church or denominational body in whose interest the school is conducted” [emphasis added]. This “in whose interest” language first appears in the 1918 legislation, but continues to be used in legislation and official guidance documents regarding denominational schools. As I have remarked elsewhere, this is very strange language indeed, suggesting that the church has an “interest” in the school, over and above its duties to pupils and the wider community.

Regarding religious instruction and observance, two opposed trends have been at work. Throughout the twentieth century, the role of religious observance, in non-denominational as well as denominational schools, has been strengthened. However, the idea of religious instruction (teaching, as true, the beliefs of one particular religion) has largely been replaced by that of religious education (learning about religion in our philosophical and cultural context). Recently, in response to public concerns, guidelines on the nature of religious observance have shifted in favour of reflection on shared values, rather than formal worship. All this, however, remains very much at the discretion of the headteacher in non-denominational schools. In denominational schools, religious observance and religious education remain firmly under the control of the religious body in whose interest the school is conducted.

Many non-denominational schools have chaplains, or even chaplaincy teams, but there is no obligation to do so. The Church of Scotland receives no special legal preference, and I almost wish that it did, since extreme evangelical groups make it their business to get involved in school chaplaincies, as in the notorious Kirktonholme fiasco, when all pupils were given “textbooks”, describing evolution as a wicked lie, by a chaplain from an extremist sect who had been advising about the school’s curriculum for eight years.

Collecting information about chaplaincy teams is difficult, except when the school chooses to display it in its Handbook. Freedom of Information requests to schools, like all such requests, are forwarded to the Council, but the Council may not have all the relevant information, and some Councils even regard this information as personal and confidential. In denominational schools, chaplains are effectively church nominees.

The 1872 Act allowed schools to continue “instruction in religion”, but did not require it. It also recognised the rights of parents “without forfeiting any of the other advantages of the schools, to elect that their children should not receive such instruction”, and more recent legislation applies this right to both Religious Observance and Religious Education. Current guidance goes further, in requiring the school to provide an educational activity of value to pupils during the time that they are withdrawn from religious activities, although it would be prudent for the parent to make this easy for the school, for example by supplying reading materials.

Note that the right to withdraw rests with the parents, although in practice many schools allow senior pupils, at least, to withdraw themselves.

The obligation to have religious observance in non-denominational schools only dates from the 1946 Act. Under this Act, a local authority can only remove this requirement when authorised to do so by a ballot of all constituents, not merely those directly involved with the school system. No authority has ever seriously considered such a ballot, despite a petition to that effect a few years ago from the Edinburgh Secular Society.

Details of religious observance and religious instruction are a matter of policy, not legislation. In 1991, the Scottish Government issued a circular saying that there should be religious observance in primary schools at least once a week, and in secondary schools at least once a month, and that this should have “a broadly Christian character”.

A major 2004 consultation, the Report of the Religious Observance Review Group (Edinburgh: The Scottish Executive, 2004), made major changes in official policy. Religious observance is now said to consist of ”community acts which aim to promote the spiritual development of all members of the school community and express and celebrate the shared values of the school community”. This could be an act of worship, if the school community corresponds to the faith community. The Report also make clear the distinction between Religious Observance and Religious Education. The form of RO is very much up to the individual school and “Head teachers are encouraged to engage in full discussion with chaplains and other faith group leaders in the planning and implementation of religious observance” (here, para. 13)

The Scottish Government is committed to ensuring that parents are made aware of their right to opt out. How much this commitment is worth, is another matter. At one time guidance clearly stated that the school Handbook should tell parents of their right to opt out, but many of them do not, and there is considerable anecdotal evidence of schools discouraging opting out, by requiring a formal letter or an interview with the head teacher, or even by telling parents that their children’s education will suffer.

The content of Religious and Moral Education (or, for Catholic schools, religious education) is again a matter of policy, not legislation. Current policy (The 2011 “religious instruction” circular, Curriculum for Excellence – Provision of religious and moral education in non-denominational schools and religious education in Roman Catholic schools) lays out ambitious goals, including “well planned experiences and outcomes across Christianity, world religions and developing beliefs and values”. The details are left to the curriculum setting and examining bodies, and to the textbook writers. This could have unfortunate consequences; one topic properly discussed in RME is religiously motivated creationism, but this may be the only encounter that pupils (and RME teachers) have with evolution, and it would be going against the admirable spirit of RME to tell pupils which one they should prefer.

That European Convention on Human Rights specifies a universal right to education, and that “the State shall respect the right of parents to ensure such education and teaching is in conformity with their own religious and philosophical convictions.” However, the United Kingdom signed the treaty with the reservation that this clause only applies in so far as “it is compatible with the provision of efficient instruction and training, and the avoidance of unreasonable public expenditure”. This is as well, since otherwise it might be open to a parent to demand that their children not be taught about evolution. Even so, the ECHR would no doubt be quoted in support of the continued existence of denominational schools, should this ever be called into question.

The Scottish Government’s 2011 circular on religious instruction states that “In Roman Catholic schools the experiences and outcomes should be delivered in line with the guidance provided by the Scottish Catholic 168 Education Service.” Parents still have a right to withdraw pupils, but “in choosing a denominational school for their child’s education, they choose to opt in to the school’s ethos and practice which is imbued with religious faith and it is therefore more difficult to extricate a pupil from all experiences which are influenced by the school’s faith character.” My own view, unfashionable in some circles that I move in, is that if you don’t want your child to have a Catholic education, you shouldn’t send them to a Catholic school. The situation here in Scotland is different from that which has recently been engineered in England, where nondenominational alternatives may simply be unavailable.

The 1918 Act specified that teachers in denominational schools must be “approved as regards their religious belief and character by representatives of the church or denominational body in whose interest the school has been conducted”. The 1980 Act inherited this requirement, although the reasons for objecting to an applicant must be stated in writing. According to the Scottish Catholic Education Service, a person’s faith and character could be vouched for by their priest, if they are Catholics, or by some other suitable person if they are not. I find this interesting, since it implies that being a Catholic is not a necessary condition of employment as a teacher in a Catholic school, yet (anecdotal evidence) this criterion seems to apply in practice. It also continues the right of the denomination to appoint a supervisor of religious instruction. This seemingly innocuous provision has serious effects, since in Catholic schools teaching about human sexual behaviour is included as part of the “Made for Love” module of Religious Instruction. Thus education on this topic is under the direction of the Council of Bishops, a committee of middle-aged middle management males pledged to lifelong celibacy.

I rest my case.

Reference: Callum G Brown, Thomas Green and Jane Mair, Religion in Scots Law: The Report of an Audit at the University of Glasgow: Sponsored by Humanist Society Scotland (Edinburgh, HSS, 2016), https://www.humanism.scot/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Religion-in-Scots-Law-Final-Report-22-Feb-16.pdf

Selected media reports:

STV: http://news.stv.tv/scotland/1344588-religious-influence-on-schools-strengthened-significantly/

BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-35674059

Christianity Today: http://www.christiantoday.com/article/religious.influence.increasing.in.scottish.schools/80854.htm

National Secular Society newsletter: http://www.secularism.org.uk/news/2016/03/religion-based-scottish-education-system-needs-to-adapt-to-social-change-say-academics

An affront to democracy; unelected Church nominees sit and vote on Council Education Committees in Scotland (and England)

A question for your Holyrood candidates

I will be asking my Scottish parliamentary candidates how, in their view, Council Education Committees ought to be selected. Should they simply consist of elected councillors, plus others (e.g. teachers) that they vote to co-opt? If not, what arrangement would the candidate prefer? And readers may also want to ask about this; I would love to hear the candidates’ answers. Why I am asking this strange question? Because of these strange facts:

The scandal

By pre-devolution law, all Council Education Committees must include three individuals nominated by Churches. One nominee is from the Catholic Church, and one from the Church of Scotland. The third is from a religious body selected by the Council, having regard to local demographics. The elected councillors themselves have no further say in the matter, nor do those they represent. Non-believers, and members of any other than the three privileged denominations, need not apply. Nor need experts in curriculum development, child health, social planning, or any other form of worldly expertise.

And just in case any of my English friends are thinking “silly old Scotland again”, did you realise that there are two such nominees on every English Local Authority Education Committee, one Church of England and one Catholic? Presumably the larger number in Scotland reflects the more fractious nature of our ecclesiastical politics:

Education Committees control a larger part of Council budgets than any other Committee. They are the ultimate employers of School Principals and teachers, as well as being represented on senior teacher selection panels. They decide on the opening and closing of schools and whether a school should be denominational or nondenominational, and control local practice in such matters as religious education, religious observance, and instruction about sex in human relationships.

The Episcopal Church, with 25,000 communicants, was offered 10 places on Committees and has filled 7 of them

The requirement for representatives of religion on these Committees dates back through Acts in 1994 and 1973 to the 1929 reorganisation of local government in Scotland, and the earlier provisions on which it was based. To a time when the formation of the public education system was fresh in the memory, and when the population of Scotland was overwhelmingly religious.*

Almost a century later, none of this is still true. According to the 2011 census figures, the largest single religious category is “None”, while only 54% of the population describe themselves as Christian. These numbers vary greatly from region to region; the legal requirement does not. The 2014 Scottish Government Social Attitudes Survey shows 68 percent of 18-24 -year-olds and 56 percent of 25-39 -year-olds describing themselves as “no religion”. So the Nones are an actual majority in the age cohorts now beginning to send their children to school. And surely no one would claim that the pre-1918 system gives the Churches an inherited right over education. We are talking about children, not property.

The role of the Church nominees is real, not ceremonial. According to the Church of Scotland itself, they hold the balance of power in 19 of Scotland’s 32 Education Committees, so that in an actual majority of Councils, the wishes of the controlling party or coalition can be overridden if these nominees side with the opposition. Given, moreover, the admirably conversational tone of much Scottish politics, their influence will not be limited to such formal occasions. And from time to time they represent the Council on teacher selection panels.

Why this matters

Space does not permit full elaboration of the case for abolition of these privileged positions, so the following incomplete summary must suffice:

The arrangement violates human rights. It excludes nonbelievers, and followers of any belief system other than the three represented, from equal participation in the process of government

It is anti-democratic. It places part of the machinery of government under the influence of individuals in whose appointment the electorate has no say. The point here is not that these individuals are religious; so indeed many elected councillors. It is that they are unelected. They sit and vote on the most important of all local authority committees, having completely bypassed the democratic process

It assumes a consensus in favour of religion that no longer exists. Nonbelievers are now the single largest group in Scotland, and an actual majority among the young

It restricts the ability of elected Councillors to co-opt individuals of their own choosing, since both law and common sense require that the Committees have a majority of elected members

It has proved difficult if not impossible to follow in practice. Freedom of Information request found that, as of July 2015, seven councils had failed to fill all positions; one (Orkney) had appointed no religious representatives; eight had filled the third Church Representative position by newspaper advertisements that had attracted only one applicant; one representative had nominated himself when asked to consult with colleagues; and for these or other reasons, in 18 out of 32 councils the process had clearly proved defective.

The Rev. David Fraser’s church quotes experts 99.9% sure that they have found Noah’s Ark (this, from his Church’s web site, is just a scale model). The Rev. David Fraser, who sits,unelected, on Clackmannanshire’s Education Committee, believes (see website) that “The vast majority of those dying are entering hell.”

It gives power to unelected individuals with extreme and unrepresentative views. I blogged on this in 2013, and the situation has not changed. The haphazard procedures described above make it easy for extreme Churches to gain the right to nominate a representative. Thus, from the limited information available on Church websites, we know that there are at least six representatives of Churches (in Clackmannanshire, Highland, Inverclyde, Na h-Eileanan Siar, North Ayrshire and Souh Lanarkshire) who believe that the prescribed Earth and Life Sciences syllabus is a pack of lies, the same number believing in the literal physical eternal punishment of those who reject Jesus, and one who believes in the curing of physical ailments by laying on of hands. For the nominees of these Churches, holding these extreme views becomes a job requirement for Education Committee membership, despite the science content of the Curriculum and the educational goals of tolerance and inclusiveness

It risks placing teachers and school management teams in an impossible position. I know of cases where a six-day creationist is simultaneously a member of school chaplaincy teams, and of the Education Committee overseeing these same schools. Consider the dilemma of a science teacher who may wish to confront him

It gives double representation to specific privileged viewpoints. If a concern arises related to the special interests of one particular religious group, constituents belonging to that group can appeal, both to their own council members, and to the relevant Church nominee

Finally, it gives the Councils an unwanted and unwarranted voice in the internal affairs of religion itself. They are forced to nominate one from the numerous religious organisations in their area, at the expense of all the others. And in the event of schism within a Church, for which there is precedent, they would be required to choose between rival claimants.

The simple remedy

A one-paragraph Act, revoking one clause of the existing legislation, is all that is needed to remove the offending requirement. If the elected councillors still wished to co-opt representatives of Churches, or the public chose to elect them to office, they would, of course, be free to do so. But imposed Church nominees on Education Committees are an indefensible anachronism, incompatible with the realities and aspirations of a modern democratic Scotland. It is time for them to go.

Footnotes:

Adapted from my op-ed in The Scotsman, which attracted this comment:

It’s a simple argument. Council education committees currently have unelected special interest members, this a legacy quid pro quo from when the churches handed over their schools to be run by the state. The issue should not be that these members are religious but that they have not been elected. Only those who have been elected should have voting rights.

* Parallel legislation regarding England specifies two representatives of religion, one from the Church of England and the other from the Catholic Church; the difference between England and Scotland presumably reflects the more fractious nature of religion in Scotland; the 1929 Act was presumably drafted just before the (partial) healing of the Great Disruption that had split the Church of Scotland since 1843.

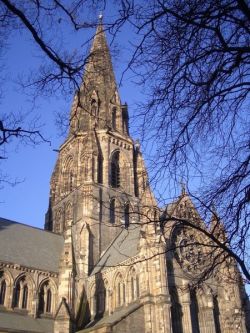

Church of Scotland offices by Kim Traynor via Wikipedia under Creative Commons licence. Committee membership as of September 2015, from FoI responses by Councils. Church history diagram by Hogweard via Wikipedia, public domain; click to enlarge or see here for full scale view. St Mary’s cathedral Church, Edinburgh, by Finlay McWalter via Wikipedia under GNU licence; church membership figures for Episcopalians as of 2013, from Church Times

The Church of England and Creationism.

Even William Jennings Bryan, at the 1925 Scopes Trial (of which more later), prosecuting under the law he had helped form that made teaching evolution illegal, admitted the probability of an ancient Earth. Now, infiltrating CofE and Church of Scotland, and overwhelming Baptist and Evangelical churches on both sides of the Atlantic, the absurdities of such Old Earth creationism have been replaced by a Young Earth “flood geology” creationism that is beyond absurd.

Peddling and Scaling God and Darwin

I have been asked about creationist infiltration into the Church of England, which has only come about in the last forty years. By Creationism I means those who reckon the earth to be only thousands of years old and that evolution has not happened. I will not discuss Creationism as such, except to say it is scientifically worthless and wrong as well as being bad theology.

Well here goes.

First consider the make-up and history of the Church of England. Right from the beginning, i.e 1540s, it was not completely Protestant, and has been called a bone half-set. Elizabeth wished to retain both ultra-protestants and semi-papists, resulting in tensions for over a century culminating with the execution of William Laud and the Civil war. After the Restoration in 1662 the Latitudinarians (fore-runners of liberals) gained the influence but from the 1730s Evangelicals began their long reign. Until about 1790 they…

View original post 2,167 more words

My Scottish friends; please write to your MSPs in support of opt-in petition; draft letter here

Dear XXX,

I write as your constituent to ask your support for Petition 1487, Religious Observance in Schools, which seeks to replace the present “opt-out” system for Religious Observance (RO) with “opt-in”. The petition and responses are at http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/gettinginvolved/petitions/religiousobservance, and the Petitions Committee will be holding its second hearing on November 12. We believe that the proposed change will end serious problems with the present system, lead to improvements in communication between home and school about the nature of RO, and help RO fulfil its aim of celebrating shared values.

The present system presumes agreement with the school’s practice of RO. Not all school handbooks even fulfil the legal requirement to state that opt-out from RO is available. Children who opt out are not properly catered for, and are made to feel exceptional, while there are examples of schools putting pressure on parents to reverse their decision, or even on occasion denying that the right to opt out exists in their school. The proposed change to opt-in would prevent such wrongs.

At present, while RO is intended to be a celebration of universal community values, it is often in practice dominated by one particular worldview, generally, in so-called non-denominational schools, Protestantism. This at a time when the number of Scots having no religious affiliation exceeds a third, and is greater than that of the Church of Scotland, the most numerous denomination.

The practice of RO varies enormously from school to school, and recent events at Kirktonholme Primary, where to parents’ dismay, creationist and anti-scientific books were distributed during RO, show how far it is at times from achieving its ideals. Such abuses would be most unlikely under the improved school-home communication that would result from opt-in.

Finally, we believe that the proposed change will reinvigorate RO by leading to general discussion of its nature and purpose, discussion that in our present diverse society is essential for its long-term survival.

Respectfully,

Petition to Abolish Church Seats on Scottish Education Committees; 10 Good Reasons to Sign

As I explained in my last post, a pre-devolution law requires three unelected church representatives as full voting members of every Council Education Committee in Scotland, and I strongly urge my friends to support the Edinburgh Secular Society petition ( to read and, if you agree, sign, click here) to change this. I recently discovered that the law also requires Diocesan representation in England, from Church of England and the Catholic Church. I suspect that the reason for having three representatives in Scotland is the fractious history of Scottish Presbyterianism.

The Rev. David Fraser’s church quotes experts 99.9% sure that they have found Noah’s Ark (this, from his Church’s web site, is just a scale model). The Rev. David Fraser sits,unelected, on Clackmannanshire’s Education Committee

Anyway, there we are, stuck (as the law stands) with three representatives of religion, whether anyone wants them or no. One chosen by (not just from) the Church of Scotland, one by the Catholic Church, and one chosen to represent local religious belief. Holding the balance of power in 19 out of Scotland’s 32 councils. This despite the fact that more than a third of all Scots no longer identify with any religion, and 65% of young Scots identify themselves as non-religious.

So what are the implications for my own chief concern, the teaching of science? In the summer of 2015, the Scottish Secular Society use Freedom of Information requests to obtain a full list of these church appointees, and how they obtained their positions. At least ten of of them give particular reason for concern.

David Fraser, Baptist, Clackmannanshire, nominated himself when asked to consult with the District’s Baptists. He represents Alva Baptist Church, which links to Answers in Genesis on its website, while David Fraser himself hails from Metro Calvary Santa Monica. This church believes in the special creation of Adam and Eve as characters in history, and a literal historical Fall that left their descendants “corrupted in every aspect of their being”. I’m not sure I like the idea of my children’s education being directed, in part, by someone who thinks they are corrupted in every aspect of their being. And, that of the 150,000 people who will die today, the vast majority are entering Hell. However, there is some good news; they think they’ve found Noah’s Ark. Perhaps the Rev. David Fraser will make sure this discovery makes it into the syllabus of his Council’s schools.

John Jackson, East Dunbartonshire, represents Kirkintilloch Baptist Church, whose web site says almost nothing about the church’s beliefs. This does not bode well, although the list of sermon topics shows a commendable concern for social justice.

Falkirk Council gives us Michael Rollo, of Larbert Pentecostal Church, an affiliate of the modestly named “Assemblies of God”, whose beliefs include biblical infallibility, bodily resurrection, and “the everlasting conscious punishment of all whose names are not written in the book of life”. Charming. The Rev. Rollo owes his position to the fact that the Church of first choice, Episcopalian, failed to answer requests to nominate.

In Fife, we have Mr Alastair Crockett, from Cupar Baptist Church, whose statement of beliefs refers to the divine inspiration of the Bible, but does not mention infallibility. Promising, and I am aware that “Baptist” is, like “Evangelical”, a broad term including many whose attitude towards science is exemplary. As always, the devil (if I may so put it) is in the details. Regarding the Rev Graeme Clark, Central Baptist Church, Paisley (Renfrewshire) I can say even less, since his church seems to have lost its website.

No such ambiguity attaches to Mark Fraser, Assistant Pastor/Youth Minister, of The Bridge Church, Irvine (North Ayrshire), sole respondent to a newspaper advertisement, which maintains that “[t]he one who physically dies in his sins without Christ is hopelessly and eternally lost in the lake of fire and therefore, has no further opportunity of hearing the Gospel or for repentance. The lake of fire is literal.” It also believes in divine healing through the laying on of hands. So now we know. He believes that anyone who disagrees with him, including a clear majority of the children whose education he is influencing, is going to suffer eternal torment, and serve them right.

The Rev. David Donaldson, of Greenock Elim Pentecostal Church, also obtained his position in response to a newspaper advertisement. He received his training at the International Christian College in Glasgow, now replaced by the Scottish School of Christian Mission, and his Church’s beliefs include the literary infallibility of the Bible, a historical Fall, the universal sinfulness of all men since that Fall, rendering man subject to God’s wrath and condemnation, and the eternal conscious punishment of the wicked.

In South Lanarkshire, we have yet another sole respondent to a newspaper advertisement, Dr Nagy Iskander, of Westwoodhill Evangelical Church. This name will be familiar to my habitual readers for his direct association with Answers in Genesis, his presence (until last August) on the chaplaincy team of Calderglen High, and his commitment to the view that evolution and creationism are equally untestable, and should therefore be discussed evenhandedly. By all accounts, including those of his intellectual opponents, Dr Iskander is a thoroughly nice guy, and if (I’m not sure) he thinks I’m gong to burn in Hell forever, I am confident that he deeply regrets the fact, unlike some.

And finally, the Western Isles. Here the Church of Scotland is represented by the Moderator of the Presbytery of Lewis, currently threatening to secede over the ordination of gay ministers. We have the Free Church of Scotland, committed to biblical infallibility. There is a Catholic representative, although on my reading of the law there doesn’t really need to be one here. And then we have the Free Presbyterian Church, which regards all other churches as having fallen away in either doctrine or practice, maintains “that the Bible is the Word of God, inspired and infallible, from beginning to end” and that “[t]he duty of the civil magistrate is to protect the Church of God”, and devotes a page on its website to explaining why Christians shouldn’t celebrate Christmas.

All of the above, remember, sit and vote on committees designing educational policy for all the children in their area, believers and unbelievers alike, whether anyone else wants them there, or not.

Original post October 2013, updated October 2016. The petition to remove these unelected clergy is live for signature and comment, by Scots and others, here until November 16 2016.

Petition: End Church nominations to Scottish Education Committees

By pre-devolution law, three unelected church representatives sit as full voting members of every Council Education Committee in Scotland. Edinburgh Secular Society is petitioning the Scottish Parliament to change this. I strongly urge my friends, especially my Scottish friends, to support this petition (link here; if you live in Scotland, take care to say so). This petition is supported by the Scottish Secular Society, the Humanist Society of Scotland, and the National Secular Society.

According to AnswersInGenesis. Dr Nagy iskander, shown here with his wife Nashwa who shares his mission, “teaches the books of the Bible in government schools as part of the official religious education curriculum,” and is “One of Europe’s most active creationists.” Dr Iskander is an unelected religious representative on South Lanarkshire Council Education Committee.

According to AnswersInGenesis. Dr Nagy iskander, shown here with his wife Nashwa who shares his mission, “teaches the books of the Bible in government schools as part of the official religious education curriculum,” and is “One of Europe’s most active creationists.” Dr Iskander is an unelected religious representative on South Lanarkshire Council Education Committee.

A pre-devolution law forces every local authority in Scotland Education Committee to co-opt three representatives of religion, whether they want to or no. One of these must be nominated by the Church of Scotland, one by the Catholic Church, and one chosen to represent local religious belief. This third representative is typically chosen from respondents to newspaper advertisements, making it very easy for Councillors who support a particular religious viewpoint to tip off their favourite denominations. The representatives of religion, although completely unelected and (apart from their parent Church) unmandated, have the vote on what is always the largest and most important of all council committees, and, according to the Church of Scotland itself, hold the balance of power in 19 out of Scotland’s 32 councils. This despite the fact that more than a third of all Scots no longer identify with any religion. That last number almost certainly under-represents the proportion of the non-religious among parents of school children, to say nothing of the children themselves when old enough to form their own opinions, since 65% of young Scots identify themselves as non-religious.

These religious representatives bring more to council meetings than the benefit of their wisdom. They will, by definition, bring a certain view of what kind of place the world is. They will, by profession, regard religion itself as a highly important aspect of life, otherwise they would not have chosen to devote their own lives to it. So when it comes to deciding how much importance to give Religious Observance, or how much time and effort the school should put into maintaining its chaplaincy team, they will have their own biased point of view. They will also have their own special interests, based on those of their Church, affecting such issues as the locating of schools, and whether or not new schools should be denominational.

Edinburgh Secular Society has published data (full details here) on the identities of the religious representatives in every Scottish council. In some cases, the identities of the religious representatives give particular reason for anxiety. My own specific concern is with the teaching of science, and the brute fact that some versions of religion flatly reject the facts of the antiquity of the Earth, and of evolution of living things from a common ancestor. Scientifically, this means rejecting the whole of earth science, astronomy and cosmology, and large areas of physics, chemistry, and even ancient history. Philosophically, it means elevating one particular highly questionable interpretation of one particular, also highly questionable, text above all other kinds of evidence.

So what does the membership of the education committees tell us? On this score, at least, the Catholic Church representatives should give little cause for concern, since the Vatican accepts the historic fact of evolution. Concerning the Church of Scotland representatives, there would until recently have been little to worry about, but this may be changing. The Church of Scotland now sends seminarists to the interdenominational Highland Theological College, which has a biblical infalibilist requirement for teaching staff and two six-day biblical literalist theologians on its Board of Governors. To an outsider, this looks like an unsavoury political deal, where the liberal wing of the deeply divided Church has agreed to this creationist infiltration, in the (probably vain) hope of being allowed, in return, to pursue more gay-tolerant policies.

Of the third (and occasionally fourth) representatives of religion, two are Church of Scotland, two Moslem, one Jewish, one Salvation Army, four Baptist, and five (from four local authorities) represent smaller evangelical Protestant groups who embrace biblical literalism. So, if you are a parent in 8 out of Scotland’s 32 council districts you might have worries about who is deciding what your children will hear at school.

As I shall show in my next posting, these worries will be more than justified.