Blog Archives

Darwin, Marx, Satan, and a mythical dedication

In 1954, at the height of the McCarthyite Red Scare, the anti-evolution preacher John R. Rice asked his audience to whom Marx had dedicated The Communist Manifesto. The answer, he shouted out, was Charles Darwin. It is doubtful whether Marx had even heard of Darwin when he and Engels wrote the Manifesto in 1848, but that is the least of Rice’s errors.

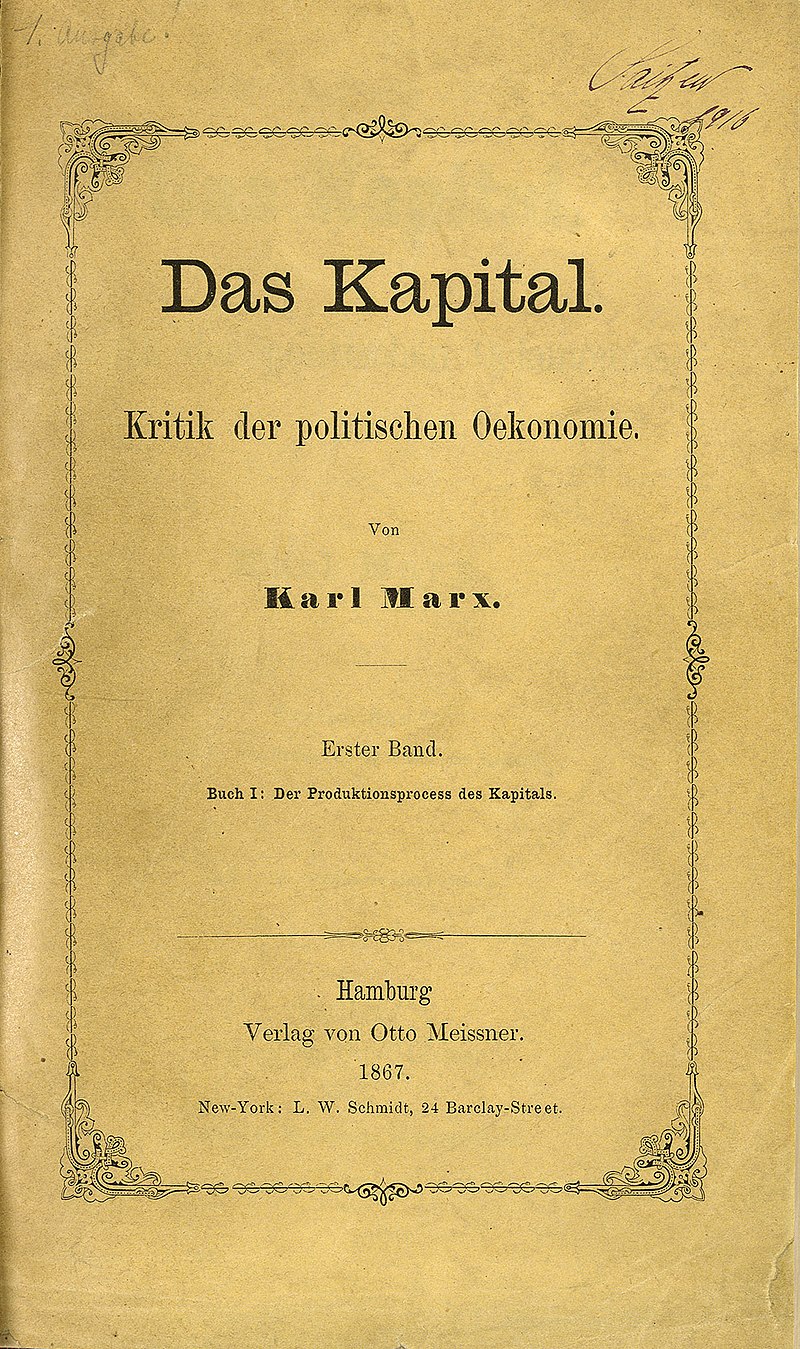

Carl Weinberg, in his excellent Red Dynamite, an overview of the deep links between evolution denial and right-wing politics in America, points out that Rice had the wrong book; he should have been referring to Das Kapital. But as we now know, even if he had been he would still have been wrong. Wrong book, wrong date, wrong author, wrong about Darwin’s response to the request to dedicate.

The matter is well summarised by Richard Carter, reporting in The Friends of Charles Darwin on a paper by Margaret Fay in The Journal of the History of Ideas. The same conclusions had been reached, independently, by Lewis Feuer, and Fay’s paper has a long discussion regarding their relative priority, and describing differences of interpretation between them. As for the belief that Marx had wished to dedicate Das Kapital to Darwin, Fay traces this to Isaiah Berlin, probably misunderstanding what Darwin actually did say in a letter to Marx.

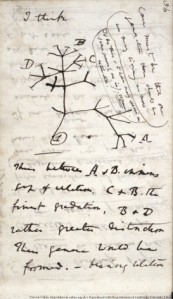

There is no doubt that Marx greatly admired Darwin, and sent him a copy of Das Kapital, which Darwin graciously acknowledged, writing, in 1873,

Dear Sir:

I thank you for the honour which you have done me by sending me your great work on Capital; & I heartily wish that I was more worthy to receive it, by understanding more of the deep and important subject of political Economy. Though our studies have been so different, I believe that we both earnestly desire the extension of Knowledge, & that this is in the long run sure to add to the happiness of Mankind.

I remain, Dear Sir

Yours faithfully,

Charles Darwin

A polite response to Marx’s gift and implied admiration, while refraining from taking any position on the merits or otherwise of the subject matter. The volume itself still languishes, with pages uncut, in the library of Darwin’s residence, Down House.

The legend that Marx had offered to dedicate his work to Darwin may also have arisen from another of Darwin’s letters, written in 1880, most probably to Karl Marx’s son-in-law Edward Aveling, with reference to Aveling’s strongly anti-religious The Students’ Darwin.:

Dear Sir:

I am much obliged for your kind letter & the Enclosure.— The publication in any form of your remarks on my writing really requires no consent on my part, & it would be ridiculous in me to give consent to what requires none. I shd prefer the Part or Volume not to be dedicated to me (though I thank you for the intended honour) as this implies to a certain extent my approval of the general publication, about which I know nothing.— Moreover though I am a strong advocate for free thought on all subjects, yet it appears to me (whether rightly or wrongly) that direct arguments against christianity and theism produce hardly any effect on the public; & freedom of thought is best promoted by the gradual illumination of men’s minds, which follow from the advance of science. It has, therefore, always been my object to avoid writing on religion, & I have confined myself to science. I may, however, have been unduly biased by the pain which it would give some members of my family, if I aided in any way direct attacks on religion.— I am sorry to refuse you any request, but I am old & have very little strength, and looking over proof-sheets (as I know by present experience) fatigues me much.

I remain Dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

Ch. Darwin

Darwin did in fact write about his changing views of religion, and at some length, in an autobiographical memoir intended only for his family, where he tells of his religious faith slipping away from him imperceptibly by degrees. He initially writes of

the extreme difficulty or rather impossibility of conceiving this immense and wonderful universe, including man with his capacity of looking far backwards and far into futurity, as the result of blind chance or necessity. When thus reflecting I feel compelled to look to a First Cause having an intelligent mind in some degree analogous to that of man; and I deserve to be called a Theist.

So to that extent he was, at that time, an advocate of what is now called Intelligent Design, although for some strange reason the modern Intelligent Design movement never lists him among their supporters.

Later, however, he wrote

This conclusion was strong in my mind about the time, as far as I can remember, when I wrote the Origin of Species… But then arises the doubt—can the mind of man, which has, as I fully believe, been developed from a mind as low as that possessed by the lowest animal, be trusted when it draws such grand conclusions? … The mystery of the beginning of all things is insoluble by us; and I for one must be content to remain an Agnostic.

The philosopher Alvin Plantinga has built an entire theory of knowledge on misunderstanding what Darwin is saying here. Darwin is pointing out that a mind arising through evolution would not be equipped to deal with problems loftier than those relating to survival. Plantinga does not seem to realise how an evolving mind would nonetheless be constrained by experience when constructing its model of the everyday world, and applies the term “Darwin’s doubt” to his own curious belief that the correspondence of that model to reality could only have arisen through supernatural intervention. For a more technical discussion of this issue, see e.g. here.

Regarding Christianity, Darwin wrote

I can indeed hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and this would include my Father, Brother and almost all my best friends, will be everlastingly punished.

And this is a damnable doctrine.

Emma Darwin, Charles’s widow, wanted to suppress this passage, on the grounds that surely nobody believed so crude and cruel a version of Christianity any more. Yet that is the version of Christianity preached by John R. Rice, with whom this piece started, and central, as I wrote earlier, following William Trollinger, to the teachings of Answers in Genesis.

The 1880 letter was written seven years later than Marx’s presentation of Das Kapital to Darwin. Moreover, it clearly relates to a work dedicated to attacking religion, which in Das Kapital is a peripheral issue. As with the first letter, we have the formal salutation “Dear Sir”, which of course does not tell us who is being addressed.

Marx’s papers were curated by Marx’s daughter, Eleanor, but the letter was almost certainly not addressed to Marx (which, as we saw before, would have made no sense regarding either content or date) but to Edward Aveling, who became Eleanor’s lover. Aveling did in fact write to Darwin in 1880, offering to dedicate his Student’s Darwin to him, and enclosing excerpts for him to consider. A contemporary review of the work by the biologist George Romanes in Nature shows that Darwin’s criticisms were fully justified:

In itself science has no necessary relation to any such belief; it is neither theistic nor atheistic; it is simply extra-theistic… Therefore, although it may be of use in the interests of “Freethought” to represent science as not merely neutral but negative in its bearings upon religion, the attempt to do so is detrimental to the interests of science; so far as it may be successful it can only tend to increase the suspicious dislike of scientific knowledge which large masses of the general public are already too apt to harbour.

And as we know, that “suspicious dislike” is as powerful and as damaging as ever.

Feuer and Fay published their refutations of the myth of Marx’s request to dedicate in 1975 and 1978 respectively, but nonetheless the myth has persisted in creationist circles. Henry Morris, co-author of The Genesis Flood, and founder of the Institute for Creation Research, referred to it repeatedly long after the story had been laid to rest. Weinberg shows a 2012 photo of a panel at the Institute for Creation Research’s Creation and Earth History Museum in Santee, California, that reads

Karl Marx is considered to be the chief founder of Communism. Although he was a professing Christian in his youth, he became an atheist and (according to some) a Satanist in college. His philosophies of history and economics were squarely based on evolutionism. In fact, he wanted to dedicate his book DAS KAPITAL to Charles Darwin, who had given him what he thought was a scientific foundation for Communism.

Satanism does seem an unlikely pursuit for the father of dialectical materialism, but according to Weinberg the suggestion that Marx had been a Satanist goes back to Richard Wurmbrand, a Romanian anti-Communist dissident. Wurmbrand’s evidence included wordplay in Marx’s juvenilia, and his 1977 book Was Karl Marx a Satanist? refers in the look-inside of its Amazon page to “Karl Marx making the secret societies symbolic gesture of the ‘hidden hand.’ ”

And according to Morris, in his The Long War against God, 1989, Satan’s involvement in promoting evolution, or at any rate a materialism which is part of the same package, dates back from Darwin through the pre-Socratics to Nimrod, the mighty hunter, whom Morris, following John Milton, blames for the catastrophe of Babel. Ken Ham, of Answers in Genesis, younger relative of the Institute for Creation Research, goes further, back to when the serpent (whom Ham, like so many, unbiblically identifies with Satan) first tempted Eve. As the Rev Michael Roberts has pointed out, Milton, rather than the Bible, is the source of much of this creationist theology.

There is an article in the October 2022 issue of Creation magazine, organ of Creation Ministries International, with the title “Darwin, Marx, and two letters”, by Russell Grigg, who like me is a chemist by training, and if anyone reading this has access to the article, I would greatly appreciate hearing what it says. There may yet be more to learn from this old story.

Repost from 3 Quarks Daily

“Gold of the gaps”, the Discovery Institute, and Intelligent Design

This from Matt Young on pandasthumb:

This from Matt Young on pandasthumb:

Gold of the gaps

Does gold have a purpose? asks an unnamed author in Evolution News & Science Today. The author goes on to observe that there is more gold on earth than astrophysicists can account for and also that gold has risen to the surface of the earth faster than might be expected. They go on to note the “availability of many essential elements at the surface of the earth …” and also discuss the use of gold in medicine. They are somewhat breathless at the discovery that the body can metabolize gold:

Gold nanoparticles, which are supposed to be stable in biological environments, can be degraded inside cells, [boldface in original]

even though, as they note, gold salts have been used for decades in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

At any rate, the article stresses the “mystery of biological gold” and claims several hints why gold may have a purpose: its abundance and seemingly unlikely transport to the surface of the earth, the ability of cells to “metabolize” [sic] gold, the fact that gold persists in the body, and the usefulness of gold for therapeutics. The conclusion of the article is Read the rest of this entry

THE ORIGIN OF DARWIN AS A NATURALIST 1809-1831

Peddling and Scaling God and Darwin

HE ORIGIN OF DARWIN AS A NATURALIST

Darwin concluded The Origin of Species with this magnificent paragraph;

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction; inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of less-improved forms…

View original post 3,712 more words

Even on his birthday, don’t say Darwin unless you mean it

How Darwin’s name is taken in vain, with mini-reviews of some of the worst offenders

Don’t say Darwin unless you mean it. Above all, don’t say “Darwin” when you mean “evolution”. It’s like saying “Dalton” when you mean atoms. Our understanding of atoms has moved on enormously since Dalton’s time, and our understanding of evolution has moved on similarly since Darwin’s. Neither of them knew, or could have known, the first thing regarding what they were talking about, and both would be delighted at how thoroughly their own work has been superseded. (Dalton of course deserves further discussion in his own right, which I will be providing in a few weeks time.)

From John Dalton’s A New System of Chemical Philosophy (1808)

Imagine if a lot of people decided that atomic theory was against their religion. We would see a parallel world of sacred science, in which molecules were “intelligently constructed”, and real chemistry would be referred to as Daltonism, or possibly, these days, neo-Daltonism. The scientific dissidents from Daltonism would invoke Dalton’s name on every possible occasion, and draw attention to the many inadequacies of atomic theory as he presented it in 1808. Dalton didn’t know anything about the forces that hold atoms together, which depend on electrons and quantum mechanics. In fact, he didn’t even know about electrons. He was muddled about the difference between a molecule of hydrogen and an atom of hydrogen. He thought that the simplest compound between two different elements A and B would have the formula AB, so that water must be HO, not H2O. And of course he knew nothing about the origin of atoms, a problem not solved until the 1950s, over a century after his death. Obvious nonsense, the lot of it!

Darwin was ignorant of transitional fossils, and in words still quoted by creationists deplored their absence as the greatest objection to his theory. He was equally ignorant about the origin of biological novelty, which comes from mutating genes. In fact, he didn’t even know about genes. And because he did not realise that inheritance occurred through genes, he could not explain why favourable variations were not simply diluted out. It would be decades after his death before we could even speculate coherently about the origins of life, and despite tantalising clues it remains a largely unsolved problem. But despite this, we have learnt an enormous amount since the publication of On The Origin of Species, and everything that we have learnt is consistent with, indeed requires, the key concepts of evolution and common descent.

So why is discussion of evolution still saturated with Darwin’s name? In part, I think, because that’s the way his opponents want it. By identifying evolution with Darwin, they continue to breathe life into the controversies of the mid-19th century. At the same time, it helps them pretend that modern biology is just one individual’s point of view, rather than a mature science based on the work of thousands of investigators. Very recently, creationists have taken to invoking Darwin himself for their cause, in such titles as Darwin’s Doubt and Darwin Strikes Back. This is an extremely powerful rhetorical tool; if Darwin was puzzled by [whatever], is that not a puzzle to us “Darwinists”? Closely related is the device of presenting creationism under the guise of even-handed debate, as when a creationist pseudo-textbook (which mentions Darwin on almost every page, but not in the index) calls itself Explore Evolution; the arguments for and against neo-Darwinism, or in the list below, where a creationist comic goes by the name, What’s Darwin got to do with it? A friendly discussion …

So why is discussion of evolution still saturated with Darwin’s name? In part, I think, because that’s the way his opponents want it. By identifying evolution with Darwin, they continue to breathe life into the controversies of the mid-19th century. At the same time, it helps them pretend that modern biology is just one individual’s point of view, rather than a mature science based on the work of thousands of investigators. Very recently, creationists have taken to invoking Darwin himself for their cause, in such titles as Darwin’s Doubt and Darwin Strikes Back. This is an extremely powerful rhetorical tool; if Darwin was puzzled by [whatever], is that not a puzzle to us “Darwinists”? Closely related is the device of presenting creationism under the guise of even-handed debate, as when a creationist pseudo-textbook (which mentions Darwin on almost every page, but not in the index) calls itself Explore Evolution; the arguments for and against neo-Darwinism, or in the list below, where a creationist comic goes by the name, What’s Darwin got to do with it? A friendly discussion …

And while we’re on the subject of unhelpful language, don’t say “theory of evolution” when you mean the well-established facts of historical and continuing change over time, and of common ancestry. And if you find yourself in the position of explaining the difference between a scientific theory (coherent intellectual structure developed to explain a range of observations), and the use of the word “theory” in everyday use (provisional hypothesis), you have blundered into a morass. Back out again.

But back to Darwin. You can see what I mean if you just look at the names of the books written by the enemies of scientific biology, from Darwin’s Doubt (Meyer, 2013) back to Darwin’s Black Box (Behe, 1996) and beyond. There are other examples, such as The Darwin Conspiracy (Roy Davies, 2006), which portrays Darwin as a plagiarist, and, while checking its details, I discovered an even more lurid book of the same name by John Darnton, which portrays him as a murderer. To be fair, Darnton does not pretend that he is writing anything other than fiction, although surely he was writing with half an eye on the creationist market.

But back to Darwin. You can see what I mean if you just look at the names of the books written by the enemies of scientific biology, from Darwin’s Doubt (Meyer, 2013) back to Darwin’s Black Box (Behe, 1996) and beyond. There are other examples, such as The Darwin Conspiracy (Roy Davies, 2006), which portrays Darwin as a plagiarist, and, while checking its details, I discovered an even more lurid book of the same name by John Darnton, which portrays him as a murderer. To be fair, Darnton does not pretend that he is writing anything other than fiction, although surely he was writing with half an eye on the creationist market.

To further test my idea, I went online to Amazon.com, and typed “Darwin” and “Darwinism” in the search window (I regularly search on Amazon, but prefer to buy from The Book Depository or Wordery). Here are some of the books by creationists that I came up with; a lot of the names were all too familiar, but I never realized that Rick Santorum had actually got his name on a book. There were also references to “materialist neo-Darwinism”, but since I don’t pretend to know what a “materialist” is, and whether I or for that matter Darwin would qualify, I decided to let those ones go.

God vs. Darwin: The Logical Supremacy of Intelligent Design Creationism Over Evolution (M. S. King, 2015): “Ever since its inception, the edifice of Evolutionary Darwinism has rested upon a foundation of sand, propped up solely by media hype, public ignorance and extreme intellectual bullying.”

God vs. Darwin: The Logical Supremacy of Intelligent Design Creationism Over Evolution (M. S. King, 2015): “Ever since its inception, the edifice of Evolutionary Darwinism has rested upon a foundation of sand, propped up solely by media hype, public ignorance and extreme intellectual bullying.”

Darwin’s Doubt (Meyer, 2013) For the fashioning of this phrase in the creationist quote mine, see here. For Donald Prothero‘s devastating review of the book, see here.

Dehumanization: A Product of Darwinism (David Campbell, 2012)

The Dark Side of Charles Darwin (Jerry Bergman, 2011)

Evolution by Intelligent Design: Debate is Over – Darwinism is Extinct (Gabor Lingauer, 2011)

The Deniable Darwin and Other Essays (David Berlinski, 2010; I have written about Berlinski here)

What Darwin Got Wrong (

The Darwin Myth: The Life and Lies of Charles Darwin (Benjamin Wiker, 2009)

Exposing Darwinism’s Weakest Link: Why Evolution Can’t Explain Human Existence (Kenneth Poppe, 2008)

Explore Evolution: The Arguments For and Against NeoDarwinism, (Stephen C. Meyer, Scott Minnich, Jonathan Moneymaker and Paul A. Nelson, 2007; this fraudulently misnamed creationist pseudo-texbook is discussed further here)

Darwin’s Plantation: Evolution’s Racist Roots (Ken Ham and A. Charles Ware, 2007)

The Edge of Evolution: The Search for the Limits of Darwinism (Michael Behe, 2007; since Behe clearly believes that biological complexity is the work of a designer who operates independently of natural laws, I include him as a creationist, although he would deny this)

Darwin Day In America: How Our Politics and Culture Have Been Dehumanized in the Name of Science John G. West, 2007)

Darwin Day In America: How Our Politics and Culture Have Been Dehumanized in the Name of Science John G. West, 2007)

Doubts About Darwin: A History of Intelligent Design (Thomas Woodward, 2007)

Darwin’s Nemesis: Phillip Johnson and the Intelligent Design Movement (William A. Dembski and Rick Santorum, 2006)

Darwin Strikes Back: Defending the Science of Intelligent Design (Thomas Woodward and William Dembski , 2006)

The Politically Incorrect Guide to Darwinism and Intelligent Design (Jonathan Wells, 2006)

Reclaiming Science from Darwinism: A Clear Understanding of Creation, Evolution, and Intelligent Design, (Kenneth Poppe, 2006)

The Naked Emperor: Darwinism Exposed (Antony Latham, 2005)

Uncommon Dissent: Intellectuals Who Find Darwinism Unconvincing (William A. Dembski, 2004)

What Darwin Didn’t Know: A Doctor Dissects the Theory of Evolution (

Darwinism, Design and Public Education (John Angus Campbell and Stephen C. Meyer, 2003) Blurb: if science education is to be other than state-sponsored propaganda, a distinction must be drawn between empirical science and materialist philosophy.

Darwinism, Design and Public Education (John Angus Campbell and Stephen C. Meyer, 2003) Blurb: if science education is to be other than state-sponsored propaganda, a distinction must be drawn between empirical science and materialist philosophy.

Darwinism and the Rise of Degenerate Science (Paul Back, 2003) Blurb: many of the constructs of evolution are based on fantasies devoid of scientific credibility.

The Collapse of Darwinism: Or The Rise of a Realist Theory of Life (Graeme D. Snooks, 2003)

Human Devolution: A Vedic Alternative to Darwin’s Theory (Michael A. Cremo, 2003)

The Case Against Darwin: Why the Evidence Should Be Examined (James Perloff, 2002)

Moral Darwinism: How We Became Hedonists (Benjamin Wiker and William Dembski (Jul 12, 2002) Abortion. Euthanasia. Infanticide. Sexual promiscuity. And it’s all Darwin’s fault.

Darwinism Under The Microscope: How recent scientific evidence points to divine design (James P. Gills, 2002)

Darwin’s God: Evolution and the Problem of Evil (Cornelius G. Hunter, 2002)

Darwin’s Demise (

Shattering the Myths of Darwinism (Richard Milton, 2000)

What’s Darwin Got to Do with It?: A Friendly Discussion About Evolution (between a bright young creationist and a stuffy stooge; Robert C. Newman, John L. Wiester and Janet Moneymaker, 2000)

What’s Darwin Got to Do with It?: A Friendly Discussion About Evolution (between a bright young creationist and a stuffy stooge; Robert C. Newman, John L. Wiester and Janet Moneymaker, 2000)

Darwinism Defeated? (J. I. Packer, Phillip E. Johnson and Denis O. Lamoureux, 1999) (Lamoureux says no, by the way)

Evolution Deceit: The Scientific Collapse of Darwinism (Harun Yahya and Mustapha Ahmad, 1999)

Tornado in a Junkyard: The Relentless Myth of Darwinism (James Perloff, 1999)

Darwin’s Leap of Faith: Exposing the False Religion of Evolution (John Ankerberg and John Weldon, 1998)

Darwin’s Enigma (Blurb: No legitimate fossil evidence exists that shows one species changing into another

Defeating Darwinism by Opening Minds (Phillip E. Johnson, 1997)

Darwin’s Black Box (Michael Behe, 1996)

In the Minds of Men: Darwin and the New World Order (Ian T. Taylor, 1996) Blurb: Creation Moments is pleased to bring you what has been hailed as the classic work on the creation-evolution issue!

In the Minds of Men: Darwin and the New World Order (Ian T. Taylor, 1996) Blurb: Creation Moments is pleased to bring you what has been hailed as the classic work on the creation-evolution issue!

Darwinism, Science or Philosophy? (Phillip E. Johnson et al., 1994)

Darwin on Trial (Phillip E. Johnson, 1991)

Darwinism : The Refutation of a Myth (Soren Lovtrup, 1987)

And so on, all the way back to The Refutation of Darwinism: And the Converse Theory of Development; Based Exclusively Upon Darwin’s Facts (T Warren O’Neill, 1879)

Darwin, God, Alvin Plantinga, and Evolution II; Plantinga in the Quote Mine and Epistemological Creationism

Prof Alvin Plantinga, of Notre Dame University, is perhaps the most distinguished critic of current views on evolution. He claims that if our conceptual apparatus is simply the product of naturalistic Darwinian evolution, it will generally give rise to unreliable results. From this premise he argues that it is unreasonable to accept naturalistic evolution, since[1] if naturalistic evolution were true, our reasons for accepting it would be unreliable. There is nothing wrong with his logic, but his premise rests on a basic misunderstanding of how evolution works.

Disclosure: around the time of the Kitzmiller-Dover trial, Prof Plantinga and I had a long e-mail correspondence, now unfortunately lost during a University mail system upgrade. I remember, however, the final exchange. He said that Behe, Dembski, and Thaxton, advocates of three different versions of Intelligent Design, had produced arguments that required an answer. In reply, I said that I totally agreed; the answer was, in each case, that they were wrong. Prof Plantinga did not reply.

Disclaimer: I have no credentials when it comes to philosophy. But let me plead in mitigation that Prof Plantinga has no credentials when it comes to evolutionary biology.

According to Plantinga, a belief is warranted when it is produced by cognitive functions working properly, according to a design plan aimed at producing true beliefs. The design plan could be produced by an agent (God, or a super-scientist), or by evolution. This convoluted definition is necessary to bypass cases that puzzle philosophers, such as, is a belief warranted when it happens to be true but we hold it for bad reasons.[2] Plantinga’s position is encapsulated in the title of his 1993 book, Warrant and Proper Function.

I have three problems here. One is the choice of words; design plan and aim have connotations of foresightful agency, and it would be better to use neutral terms such as adaptationand tendency to produce. The second is circularity; how do we define proper function, if not in terms of giving warrant to beliefs when appropriate? The third, which is really a consequence of the second, is that it is useless in real disagreements, because it begs the question. For example, Prof Plantinga tells us that he possesses a sense of the divine, which he regards as a warrant. But how can he know that this is a warrant, unless he already knows that this sense is leading him towards the truth? And what, then, of Darwin’s objection (Part I); how can we have confidence in the beliefs that this sense induces, when those who claim to possess it differ so forcibly among themselves?

Plantinga is better when dealing with the limitations of our senses. He raises the interesting possibility that while they are not perfect, they are good enough, and that their deficiencies may represent a trade-off between speed and accuracy. This, I suggest, explains some shortcomings but not others. For example, in perspective illusions, such as the parked car illusion, we incorrectly perceive the image of the object further away from us as larger. This is a small price to pay for the ability to judge the real size of distant objects. There are other illusions, such as the disappearing dots, that have no obvious function, but are presumably byproducts of a generally efficient image processing system. There are, however, defects that can only be understood in terms of our evolutionary history. Thus, notoriously, the nerve connections to the mammalian retina run in front of the light-detecting cells, obscuring the view, and there is also a blind spot in each eye, where the optic nerve passes through the retina. If a freshman engineering student came up with such a design, we would gently suggest that he considered changing his major. After all, it doesn’t have to be like that; in the octopus eye, the parts are the right way round.

One of Plantinga’s examples inadvertently illustrates how evolution actually works. He considers[3] the case of an individual with extremely low blood pressure, and a fragile aorta. The low blood pressure restricts his physical activity, but if it rose to what is considered normal, his aorta would burst and kill him. So is the heart acting properly in keeping his blood pressure low? The answer would seem to be, yes, if and only if his design includes a mechanism by which a damaged aorta limits cardiac activity. (Much as our body temperature control system includes a mechanism that causes fever when we are fighting off disease.) For Plantinga, the heart/aorta example illustrates that we can only define proper function for an organ, including a human organ, in terms of a pre-ordained plan. On the contrary, I would claim, it illustrates the artificiality of imposing, on the complexity of biological forms, the simple criteria more appropriate to artefacts.

Now consider a primitive organism with very little in the way of blood vessels. Such an organism might have a very simple heart, encouraging circulation of fluid. There would be an adaptive advantage in channeling this blood flow, and once that happens, there would be further advantage in improving the performance of the heart. The heart and the circulatory system are under a selection pressure to improve, but only step by step. This is because there would be no advantage, and some cost, if one were to get too far ahead of the other. One can imagine further elaboration, if the creature develops separate organs for exchanging carbon dioxide in the blood for oxygen. Indeed, something like this seems to be what actually happened. A mutation in advance of the proper context would be lethal; a double-circulation heart could not function properly in a codfish. So if we are to apply the concept of proper function to organisms, it needs to be set in its evolutionary context (I do not expect Prof Plantinga to agree).

Throughout, Plantinga makes things far more difficult for himself by his rejection of the natural power of evolution. He makes heavy weather, as philosophers are bound to, of the “problem” of how we know that others have minds. As Plantinga reminds us, this is not a matter of ordinary logic or inference. After all, we are arguing from analogy with our experience of ourselves, i.e. from analogy with a single example. Indeed, unless we suffer from autism, we believe in other minds from the cradle, without arguing about it at all. So when Plantinga discusses how we come to have this belief, or why we should trust it, he can give no explanation other than Providence. However, we are social species, and both survival and mating opportunities depend on social competence. Thus there is strong evolutionary pressure to develop an adequate theory of other minds. There is good evidence that our brains contain “mirror neurons”, which respond to other people’s movements and gestures in the same way as to our own, bringing us as close as separate individuality allows to sharing other people’s sensations. But even without such knowledge of mechanism, we would be well aware, as philosophers have been since Aristotle, of the vital importance to each of us of insight into the minds of others.

The last chapter of the book is what drew it to my attention, with its claim that we cannot have warrant for believing in naturalistic evolution. For the most that naturalistic evolution could guarantee, is behaviour that increases fitness,[4] and Plantinga claims that there is no good reason to suppose that such behaviour requires true belief.

At this point, Plantinga commits a blatant act of distortion by quote mining, of the kind all too familiar to students of the creationist literature, but surprising in a scholar of his stature. He manages to invoke Darwin himself to support his position, with this excerpt from a letter to William Graham:

With me the horrid doubt always arises whether the convictions of man’s mind, which has been developed from the mind of the lower animals, are of any value or at all trustworthy. Would any one trust in the convictions of a monkey’s mind, if there are any convictions in such a mind?

The quotation is genuine, but the meaning is completely distorted, by suppressing its context. Consider the passage in full:

Nevertheless you have expressed my inward conviction, though far more vividly and clearly than I could have done, that the Universe is not the result of chance. But then with me the horrid doubt always arises whether the convictions of man’s mind, which has been developed from the mind of the lower animals, are of any value or at all trustworthy. Would any one trust in the convictions of a monkey’s mind, if there are any convictions in such a mind?

So the question is very narrow and specific; whether we can trust minds evolved from those of animals when they lead us to believe that the Universe had a creator. In Part I, I gave two other examples of Darwin showing similar reticence, because of how our minds evolved. But in both those cases, Darwin is addressing exactly the same question as here, which must have preoccupied him over many years. There is no honest way of recruiting Darwin to support the view that our evolved animal nature makes our minds unreliable on any lesser topic. Yet Plantinga manages to say (p 219[5]), almost immediately after his truncated quotation,

Darwin and Churchland seem to believe that (naturalistic) evolution gives one a reason to doubt that human cognitive faculties produce for the most part true beliefs: call this ‘Darwin’s Doubt’ (emphasis added)

The expression “Darwin’s Doubt” may well be familiar; Stephen Meyer chose those words as the title of his recent book in which he presents a long since deflated[6] perspective (see here and here and here and, if you have access to Science, here) on evolutionary change in the Cambrian.

But let that pass.

It is repeatedly clear that Plantinga understands nothing about how evolution works. For example (p 204) he imagines a sadistic dictator “inducing a mutation” into his enemies, which condemns them to a life of pain, and converts their visual fields to a shadowy green screen. He then asks, if possessing this mutation is made a condition for those enemies to breed, whether defective eyesight is now proper function. In reality, it is impossible to induce mutations in individuals who already exist, and the kind of change involved would in any case, even if possible, take many generations. Compare this “mutation” with the distortion actually induced in some pedigree dogs, which have been bred to have faces so flattened that they have difficulty breathing. But this took repeated selection, and close control of bloodlines. (And I would add that the conflict in both these cases between natural and artificial selection once again shows the problems of applying the concept of proper function to organisms.)

In a deservedly much-mocked passage (pp 225 ff), Plantinga tries to describe how a deeply mistaken worldview could still enhance fitness. For example, what if someone thought that it was delightful to be mauled by a tiger, and, at the same time, that the best way to ensure being mauled was to run away from it? Such a combination of beliefs would lead to survival-inducing behaviour, even though each of the beliefs was mistaken. But for this to happen without going through a lethal intermediate stage, each of the mistakes would have to occur in a single step, and both of them would have to happen at once; an unlikely coincidence of events improbable enough in themselves. If Plantinga doesn’t see the problem, I suspect that he has failed to appreciate the step-by-step nature of evolutionary change.

The evolutionary approach, incidentally, defines a role for pain, as Darwin realised (see Part I), and this role is, precisely, to induce correct beliefs about what is harmful. Plantinga’s account of beliefs does not require such preliminaries, and so the problem of suffering is much more acute for him than for a Darwinian.

Back to Darwin’s letter. When it comes to the mundane realities on which survival depends, there are indeed circumstances where we would “trust in the convictions of a monkey’s mind”. We know that monkeys are good at detecting predators, fear them, and signal that fear to each other. If we were in the jungle surrounded by monkeys, and they suddenly show signs of having detected danger, we would be foolish not to pay attention.

I have spoken of monkeys feeling fear. Yet a follower of Descartes would deny that animals have any feelings at all. How could I convince him? Perhaps by such evidence as the monkeys’ facial expressions and vocalisations, how these affect other monkeys, changes in activity in different regions of the brain, adrenaline release, blood flow, and skin temperature, all compared with the effects of fear in humans. Then what about less intelligent animals? Pursuing this route, we will soon find ourselves refining or breaking down the concept of “fear”, and embarking on a research programme, or indeed a family of research programmes, straddling the frontiers between ethology, evolutionary psychology, and philosophy. Such programmes are already well under way.

Our conceptual apparatus is indeed unreliable, but this is just what naturalistic evolution would lead us to expect. For the failings are most evident in areas where our errors would have inflicted the least damage on our fitness, and might indeed have enhanced it.

Such failings are numerous, and here are a few examples. Our common sense (or, as Bertrand Russell called it in Mysticism and Logic [free download here], our intuition) is most reliable on matters of immediate concern. Intuition tells me that I am sitting on a solid chair, in a room that is not moving, and only recently, in evolutionary terms, was it discovered that the chair is mainly empty space, and that the room that is moving eastward at several hundred miles an hour. I see patterns that are not there in reality; but better to see a tiger that isn’t there, hiding in the long grass, than to fail to see a tiger that is. As an infant, I understand physical events in terms of purpose and agency, rather than physical causation, and in some of us this tendency persists into adulthood. No surprise, since as an infant my very survival depends on interacting with other people, and getting them to care for me. I believe in the tribal gods, because this intellectual sacrifice qualifies me for membership of the group, with access to reciprocal altruism and reciprocal trust (see Jared Diamond’s The World Until Yesterday for more on that last theme). And those last few suggestions may or may not be true, but are at least credible, and suggest further research programmes of their own.

Given these failings, how, if at all, can our scientific beliefs be warranted? In 1520, science taught that the Earth was fixed, in 1820 that species were fixed, and in 1920 that the continents were fixed. Few people would now expect to see these views reinstated. So did they have warrant at the time? If they did, how much is a warrant worth? If not, how can we claim that our current beliefs are warranted? These are interesting and important questions, but not, I think, the questions that Prof Plantinga addresses.

Moreover, the problem of warrant is most acute in the very area where Prof Plantinga seems most certain of his own beliefs, namely religion. Here, all believers would claim warrant. But their beliefs are so diverse that, as a matter of arithmetic, most (if not all) of them must be mistaken. Yet here, surely, is the area where an Abrahamic God, desirous of being loved and worshipped, would have been most concerned to design us with access to sound knowledge of His reality.

It is not the naturalistic evolutionist who should be troubled by the problem of reliability, but the Intelligent Design creationist.

Photo by Jonathunder through http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:AlvinPlantinga.JPG under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. An earlier version of this post appeared here on 3 Quarks Daily

[1] He devotes some 20 closely argued pages to this logical step, but I think I have captured the drift.

[2] If I understand him correctly, Plantinga would say that it is still warranted as long as we are in no position to realise that the reasons are bad.

[3] I have changed the details slightly, in order to make the situation more plausible.

[4] Plantinga generally refers to survival advantage, but fitness, the ability to survive and produce offspring that are themselves fit, is what actually matters.

[5] Page number references are to Warrant and Proper Function, print edition, OUP 1993.

[6] The “Cambrian explosion” isn’t what it used to be.

Darwin, Wallace, Evolution, and Atheism (Part II of Bears, whales, God, Darwin, and Peter Hitchens)

[For Part I, see here]

Peter Hitchens, younger brother of the late Christopher, says in the notorious London Daily Mail that the implication of evolution “is plainly atheistical, and if its truth could be proved, then the truth of atheism could be proved. I believe that is its purpose, and that it is silly to pretend otherwise.” Pat Robertson claims that “the evolutionists worship atheism.” Richard Dawkins tells us that he lost his faith in God when he learned about evolution, the claim that evolution is intrinsically atheistical is used repeatedly by advocates of creationism, including that bizarre oxymoron, “scientific creationism”, and the Discovery Institute’s Wedge Document describes it as part of a malignant materialism that debunks traditional views of both God and man. Discovery Institute fellows also coached Ann Coulter, who went on to tell us that evolution is itself a discredited religion, related to the mental disorders of liberalism and godlessness.

Yet from the very outset there have been believers who actively welcomed evolution. Asa Gray, the botanist to whom Darwin dedicated his own book Forms of Flowers, saw evolution as the natural process through which God worked. Charles Kingsley, the Christian social reformer and historian now best remembered for The Water Babies, wrote appreciatively to Darwin, on previewing The Origin of Species, that a Deity who created “primal forms capable of self development” was “a loftier thought” than one who had created each kind separately. In our own time, we have evolution theology and Evolution Sunday. Ken Miller, a committed Catholic, is prominent as molecular biologist, textbook writer, and legal witness on behalf of evolution, while Dennis Venema’s postings on the website of BioLogos, an organization dedicated to the acceptance of science from a Christian perspective, are model expositions of evolutionary science.

Against this background, it may be helpful to look at the religious views of Charles Darwin himself, and also those of Alfred Russel Wallace, the two independent originators of the concept of evolution as the inevitable outcome of natural selection. Warning: this post will be longer than most. The Victorians do not lend themselves to sound bites.

Darwin’s private Autobiographies include a short but revealing chapter on religious belief. This the family regarded as so contentious that it was not made public in full until 1958. Darwin initially contemplated becoming a clergyman. He tells us that he “did not then in the least doubt that strict and electoral truth of every word in the Bible”, and was much impressed by Paley’s argument from the perfection of individual organisms to the existence of an intelligent creator, He was still quite orthodox while on the Beagle, but in the two years after his return he reconsidered his position, and gradually came to reject orthodox religion on historical, logical, philosophical, and indeed moral grounds. As he later wrote,

“I can indeed hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and this would include my Father, Brother and almost all my best friends, will be everlastingly punished.

And this is a damnable doctrine.”

As for the implications of science, Darwin’s conclusions are interesting. “The old argument of design in nature, as given by Paley … fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered…. Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.” Regarding what he called, despite the deaths of three of his children, “the generally beneficent arrangement of the world”, this he explained as itself the result of evolution. In order to survive, creatures must be so constituted that pleasure outweighs pain and suffering, which “if long continued, causes depression and lessens the power of action.” As for the opposite argument, “The very old argument from the existence of suffering against the existence of an intelligence as cause seems to be a strong one; whereas… the presence of much suffering agrees well with the view that all organic beings have been developed through variation and natural selection.” In short, the argument from the goodness of the world and the counter-argument from suffering both fail, since the capacities to experience pleasure and suffering, and the balance between them, are themselves explained as evolved adaptations.

One argument, however, retained conviction at the time when he was writing On the Origin of Specie, namely “the extreme difficulty or rather impossibility of conceiving this immense and wonderful universe… as a result of blind chance or necessity.” Notice that Darwin makes a clear distinction, which today’s “Intelligent Design” advocates systematically blur, between Paley’s argument from the design of particular things (rejected, as we saw earlier), and the more powerful argument from the possible presence of design in the universe as a whole. The latter he finds convincing enough to say, at the very time that he was composing On the Origin of Species, that “I deserve to be called a Theist”.

Later, Darwin wonders, “can the mind of man, which has… been developed from a mind as low as that possessed by the lowest animal, be trusted when it draws such grand conclusions? … The mystery of the beginning of all things is insoluble by us, and I for one must be content to remain an Agnostic.” Our minds evolved to enable us to deal with commonplace reality, and we must doubt whether they are adequate instruments for speculating so far beyond that. “Agnostic” was a term then newly coined by his friend and prominent supporter, Thomas Huxley, and refers, not to a wishy-washy uncertainty, but to the principled conviction that there was no adequate way of deciding the question.

Alfred Russel Wallace is a much more complicated case. He seems to us self-contradictory and changeable, an opponent of the supernatural who nonetheless took Spiritualism seriously. He was also much more wordy than Darwin; his autobiography runs to two thick volumes. I have therefore relied mainly on secondary sources,[1] together with his review of Lyell’s writings on geology, in the April 1869 issue of The Quarterly Review[2], and his 1871 reply to critics.

In his teens, Wallace came into contact with the reformist ideas of Robert Owen, and abandoned conventional religion, with its emphasis on original sin, for a belief in human improvability based on the natural sense of justice. Throughout his adult life, he described himself as a Socialist, and wrote a book in favour of the nationalization of land. He seems to believe in a Creator, and indeed advances, as an argument in favour of evolution, that separate design for every creature would reduce that Creator to the level of a second-rate craftsman[3] (compare Charles Kingsley’s comments, above). However, only two years before formulating his own version of the theory of natural selection, he had written of how far, in his view, the beauty and diversity of the forms of living things goes beyond what could, for him, be explained in terms of their requirements.[4]

This last conclusion may help make sense of his 1869 review of Lyell, in which he asserted that there were things about humanity, in particular, that could not be explained by natural selection. Abstract thought, moral sense, and the design of the hand, all as much present in what he called the savage as in civilized man, seemed to him superfluous to the requirements of the savage’s life. This despite having lived among such savages while collecting specimens, and observing the demanding nature of their lifestyles, the skill of their toolmaking, and the subtleties of their social organization. He also makes the linked arguments that evolution cannot explain the development of consciousness (for contrary opinions, see Dennett’s Kinds of Minds and Cairns-Smith’s Evolving the Mind), and that materialism cannot explain how consciousness could exist at all (here, I think, Wallace is referring to a problem that we are no nearer solving now than we were then).

But does this mean that he was willing to embrace the supernatural? Quite the reverse! In his answers to critics, he says very plainly that he does no such thing. What he does do, is reject materialism. There is more in the universe than matter, but nothing that is beyond the scope of natural science.

So what of Peter Hitchens’s (and, for what it’s worth, Pat Robinson’s) claim, given that neither Darwin nor Wallace could be pigeonholed as atheists, and that Wallace was not even a materialist? Totally false. Grossly insulting to the entire scientific community, portrayed as choosing its key concepts according to an ideological agenda quite outside science. As I said before regarding all evolution denialism, dependent on a conspiracy theory. And a warning to all of us; if this is typical of journalistic comment in the areas that we know about, like science, how should we regard such comment in areas that we cannot so readily examine, like Syria?

There remain some serious questions. Is it possible to accept evolution without being an atheist? Quite obviously, yes, as Darwin, Wallace, and many examples listed here clearly show. But human psychology is notoriously quirky and tolerant of self-contradictions). So, as a matter of logic, is religious belief compatible with the acceptance of the fact of evolution?

The answer, surely, must depend on the kind of religion, and here my sympathies lie entirely with their Evolution Sunday crowd. Evolution demolishes one version of the argument from design, but even when I was a believer I did not find that version convincing. And, for the reasons spelt out over the past 150 years by Kingsley, Darwin, and many others, evolution poses no new problems for religion in general, and indeed may blunt some of the traditional arguments used against it.

What is not consistent, either with present-day scientific knowledge, or with any kind of scientific approach to reality, is a religion dependent on an overriding belief in the literal truth of its sacred text. Such a position renders impossible any sensible discussion of evolution, or of nature in general, or, indeed, of God.

[1] See e.g. Helena Cronin’s The Ant and the Peacock, which discusses Darwin’s and Wallace is different views on sexual selection and cooperation; Natural Selection and and Beyond, ed. Charles H Smith and George Beccaloni.

[2] Confusingly indexed in QR under Lyell, not Wallace.

[3] Smith and Beccaloni, p. 327.

[4] Ibid p. 370.

Bears, whales, God, Darwin, and Peter Hitchens (Part I)

Can bears turn into whales? Peter Hitchens (PH) asks this question in two successive instalments of an anti-evolution tirade of the kind that gives ignorance a bad name. Normally I would not have bothered with such nonsense, especially since Jerry Coyne at WEIT has already dismembered what with PH passes for reasoning in greater detail than it deserves. However, PH does raise an interesting question or two, and makes one assertion is so breathtaking in its combination of arrogance and ignorance that I cannot forbear from discussing it. Let me deal with these matters in turn.

The first question is, can bears turn into whales? The suggestion is based on a remark by Darwin, in the first edition of On the Origin of Species, which he dropped it in later editions as being too speculative. However, PH still chooses, over 150 years later, to cite it as evidence that Darwin’s whole research programme, and by implication the entire structure of the life sciences as they have developed since that time, is really very silly. As to why we all indulge in such silliness, PH’s answer, which I will analyse later, is as ridiculous as it is insulting.

The answer to the question, by the way, is no. Of course, no presently existing species is capable of evolving into another presently existing species, any more than PH is capable of evolving into his late lamented brother, nor would Darwin ever have suggested such a thing. If we rephrase the question a little more precisely, do bears and whales share a relatively recent common ancestor, the answer is still no. Bears do in fact share a relatively recent ancestor with seals and walruses, but their last common ancestor with whales was back in the Cretaceous.

The obvious question then arising is this: if whales are not related to bears then what are they related to? Forty years ago, we didn’t have a precise answer to that question. Now we do, and PH could have found it easy enough, just by looking up whale evolution in Wikipedia. And while PH is understandably concerned about erroneous assignments, since the only fossil he seems to know about is the Piltdown forgery, Wikipedia will also provide him with a list of 43 separate extinct families of precursors of modern whales. But perhaps PH is a Wikipedia snob, or perhaps these articles, replete as they are with terms like “artiodactyl” and “cladogram”, are above his technical reading level. In the latter case, I would refer him to an excellent National Geographic article; in the former to either of two recent but more technical reviews, here and here. I will be writing about whale evolution at much greater length elsewhere, showing as it does a beautiful coming together of three separate lines of evidence; from the fossil record sequence, from anatomical homologies, and from molecular phylogeny.

My point here is a rather obvious one. PH admits that he is ignorant about evolution. Nothing to be ashamed of there. After all, he is a busy man, and has his own priorities, and if he can’t find the time to learn what kind of place the natural world is, and how we fit into it, then that’s his own business. But what he should be most deeply ashamed of, is his decision to write, not once but twice, about such a subject without first bothering to inform himself.

Despite his self-proclaimed ignorance, PH claims to have penetrated the motivation of the scientific community in its acceptance of what he describes, in rather simplistic and old-fashioned language, as “the theory of evolution by natural selection.” What he tells us of this theory is that the motivation is fundamentally theological, or rather, anti-theological. To quote, “I will re-state it, yet again. It is that I am quite prepared to accept that it may be true, though I should personally be sorry if it turned out to be so, as its implication is plainly atheistical, and if its truth could be proved, then the truth of atheism could be proved. I believe that is its purpose, and that it is silly to pretend otherwise.” [My emphasis]

So this is a clear statement of what PH considers to be the purpose of the theory; not to make sense of nature, as we scientists pretend, but to prove the truth of atheism. Well, questions of motivation are always interesting, if difficult to settle, but in this particular case we happen to be in a position to decide the truth or otherwise of PH’s claims. The theory of evolution by natural selection was first clearly formulated by two separate individuals, initially working independently, Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin. We know a great deal, in both cases, about their attitudes to religion, and Darwin in particular has left us a detailed description of how his views changed over time, as a result in large part of the evidence that he collected while developing and testing his theory. Both these great scientists changed their opinions on religious and spiritual matters during their working lives. Neither developed their theories in pursuit of a theological agenda, and if they had done so, that would have amounted to professional malpractice. The reality is very different, much more interesting than anything PH could have imagined, and we will return to this in the next part.

Don’t say “Darwin” when you mean “evolution” (part 1)

Part I,Dalton and Darwin

Don’t say “Darwin” when you mean “evolution”. Don’t say “theory of evolution” when you mean the established historical facts of change over time and common descent. And above all, don’t say “Darwin’s theory of evolution” except in the historical context of the evolution of ideas. If you do, you are guilty of scientific, logical, historical, and pedagogical errors, and playing into the hands of our Creationist opponents.

Dalton is to the modern atomic theory, and the modern atomic theory is to chemistry, as Darwin(not to forget Wallace) is to evolution, and as evolution is to biology. But we don’t call our present perspective on atoms “Dalton’s theory”, and indeed, unless we are speaking historically, it sounds odd to even talk about “atomic theory” when we discuss atoms. So why should we refer to “Darwin’s theory”, and indeed why should we talk about the “theory of evolution” when we really mean the fact that evolution has taken place? I argue here that we shouldn’t, and that, given the ongoing opposition to the central facts of biology, it is actively damaging to do so. Read the rest of this entry